Published on April 30, 2019

Written by Alexa Battler

Written by Alexa Battler

News & Media Assistant, University of Toronto Scarborough

I’ve noticed many people in communications believe they need a DSLR camera to produce high-quality pictures, while neglecting the powerful ones sitting right in their pockets.

Don’t get me wrong, I love my DSLR (or digital single-lens reflex camera) — a Nikon D7200. She’s not flashy, but damn it, she gets the job done.

Then there’s the Nikon D850. I work as the news and media assistant in Marketing and Communications at the University of Toronto Scarborough. I take photos for articles, the school’s social media channels, advertising material, internal use and so on. I get to do it all with a D850 — the heavyweight, full-frame beauty that I openly call “my baby” in front of people at work.

But the value I see in these cameras is largely driven by the fact that I’m a huge nerd for them. As a content creator, I have to argue that in many cases, DSLR cameras are actually completely unnecessary.

The case against DSLRs

One of the DSLR’s greatest strengths for reporters and photographers may be what makes them deceiving and unnecessary for others — they look fancy and expensive, which projects (apparent) legitimacy.

But all that glitters is not gold. Having a DSLR will not give you the ability to use it, though it may convince people you can on reputation alone (which is not necessarily a good thing, trust me). DSLRs also represent a steep learning curve, and the more detail a camera lets you control, the more you need to know to properly use it.

Another hurdle lies in the cost — camera bodies, lenses, flashes, tripods, they add up incredibly quickly. And then there’s the infrastructure needed for each step after snapping the picture. The photos must go from a memory card to a computer with enough storage and RAM to view and alter them, then to a decently pricey editing software, likely Photoshop or Lightroom (while there are cheaper and free softwares, you get what you don’t pay for).

After all that, how do you then share your photos, which may have an enormous file size depending on your camera and export decisions? These are all factors and questions to consider before thinking of buying or even using a DSLR. While editing photos can be a saving grace, this stage of the process is way too late to be asking yourself why you took a picture. The same thing applies when weighing the purpose of your image-capturing goals with your camera options.

Take it from a photographer — the technical side of photography is not that hard. It’s a science that essentially guarantees results for those with perseverance and tact. The hard part is the artistry behind the photo, and the ability to craft an image that will mean something to someone.

The only thing you can do to truly improve both the technical and artistic sides of your photography is practice (or experiment, if you will). You have to continuously tweak camera settings, strategically use light and apply simple fundamentals, over and over again.

Having a DSLR will not give you any of the skills you need any faster. But fear not — there is a piece of technology that you most likely already have and know how to use, which can take the quality of photos you need and share them instantly.

The case for smartphone photography

Not everyone has a DSLR. But 76 per cent of Canadians have smartphones. The benefits of using those smartphones as cameras are obvious — they are convenient, lightweight, less expensive and you already know how to use it (at least somewhat).

Again, photography is not that hard, it’s mostly just a science. The principles I use to take photos with my DSLR are the same fundamentals (such as use of light and composition) that I use when taking photos with my smartphone. It’s all just science and practice, honed to support your artistic vision.

Smartphone cameras are also giving their users an increasing amount of control in their settings. Using the “pro” or “manual” mode (under whatever name it goes by on your phone) will let you adjust the same three settings that are the backbone of all photography (ISO, depth of field and shutter speed).

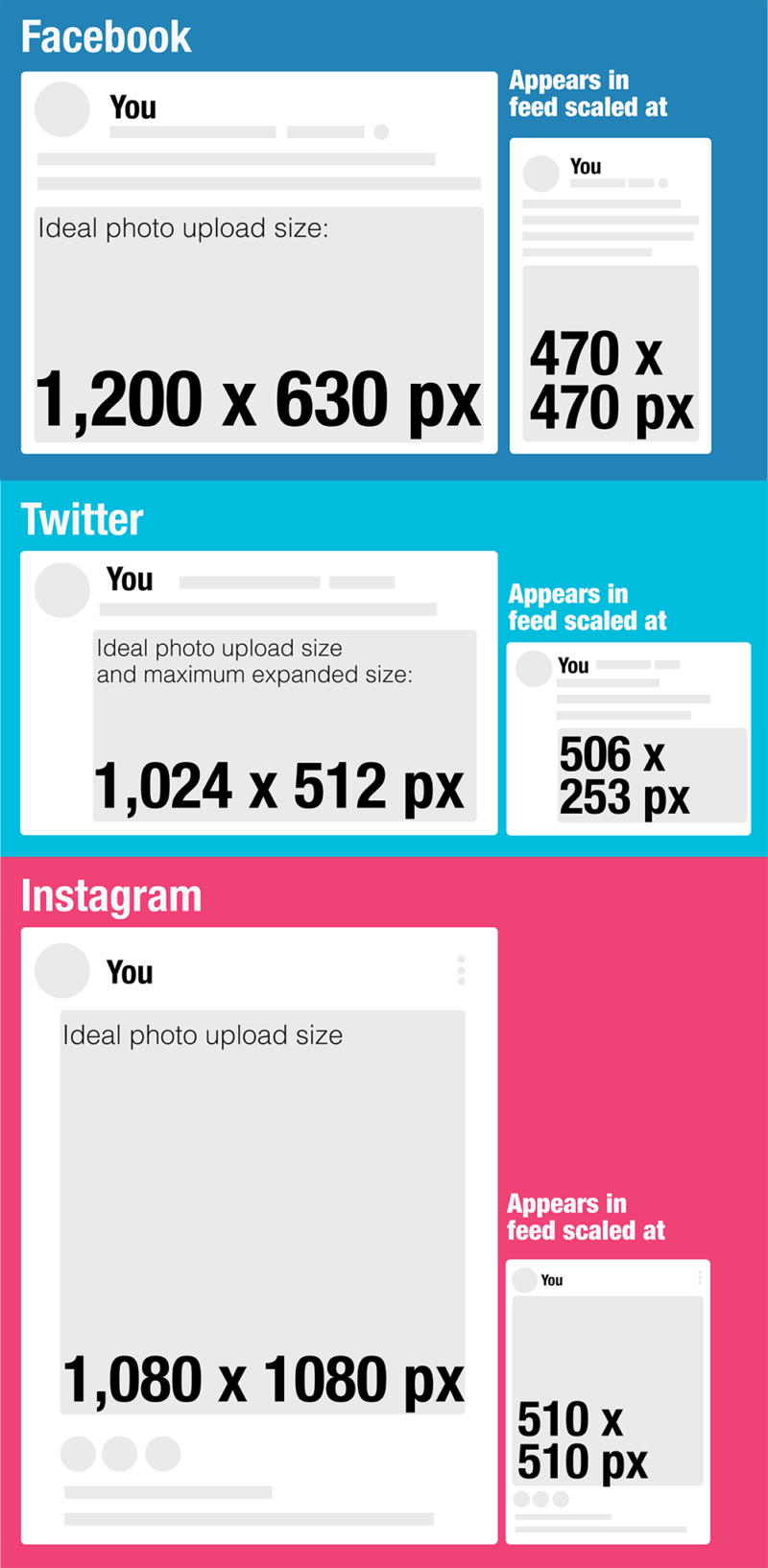

Perhaps most importantly, smartphones are streamlined to post to social media. Working in communications means most of the images I take go straight to the major social media platforms: Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. On a phone, posting to social media is just about as easy as it gets — the platforms themselves are built to seamlessly access your phone’s photos and post them.

Some DSLR cameras have come out with features offering direct posting to social media channels, such as Facebook and Instagram. But the main benefit of a DSLR, a greater degree of control over your images, is essentially lost by posting an unprocessed RAW image, which is then compressed into a fraction of its original size by social media.

Meanwhile, smartphones photography is self-contained — that is, it requires essentially no additional infrastructure. With my smartphone, I can take my pictures, pick my best ones, edit them (even in Photoshop, thanks to the fairly impressive app) and post them to social media without even needing to use my other hand, let alone a computer.

On a DSLR, not so much. I find myself spending a lot of time getting photos off my camera and on my phone or laptop so I can view, edit and post them. I won’t complain about how glitchy the mobile Nikon and Cannon apps are, but in my experience, the major camera brands just haven’t figured out how to easily and consistently get photos from a camera to a device that can post or send them.

While most new DSLRs come Wi-Fi-equipped, you may notice that moving a lot of enormous, high-resolution files takes a long time, eats a lot of space on your phone or computer and requires a very stable internet connection (if the apps work for you in the first place).

Your workflow with a DSLR will probably involve you accessing your images like this:

Camera → Memory card → Card reader (another expense if you’ve got a newer Mac) → Computer → Editing software → Social media platform

That lack of streamlining and the amount of additional technology needed are perhaps the biggest blows to the value of DSLRs in modern communications work. (If Nikon and Canon ever figure their apps out, I’ll gladly print this segment out and eat it.)

The technical reason why you don’t need a DSLR

I know what you’re probably thinking: “OK, smartphones are easier for photography, but the images won’t be as high resolution as they are with a good camera.”

My reply: “Yup, and you better hope they’re not.”

To truly understand why smartphone cameras can be an adequate replacement for a DSLR, we have to start at the smallest level: pixels.

Carl Sagan narrated it best in The Pale Blue Dot, over a stunning, slowly zooming shot of the Earth as seen from space: “Look again at that dot. That’s here, that’s home, that’s us.” That’s all photos are — a lot of dots, called (you guessed it) pixels.

There are many, many other factors that contribute significantly more to image quality and which cameras suit which contexts. Resolution is actually a vastly small piece of the puzzle when considering sensor quality, lens quality, low-light performance, colour depth and so on. But pixels are a key part of understanding the contextual needs and limitations of taking and sharing modern photography.

To put it simply, the more pixels, the more detail in your photos, the more you can zoom into them and retain details (making CSI’s zoom-and-enhance bit slightly more plausible). Consider the infamous line from Clueless: “She’s a full-on Monet … From far away, it’s OK, but up close, it’s a big ol’ mess.”

Megapixels (you may be more familiar with its shorthand, MP) are the equivalent of one million pixels, completely blowing Monet out of the water. This means an image taken with a 12-MP camera will have 12 million pixels, while an image taken with a 50-MP camera will have 50. Million. Pixels.

And most of them will never survive.

Realistically, if you’re in communications, you’re probably posting a fair amount of your images on social media. Posting on social media is going to resize your photos and destroy a staggering majority of those pixels as it squishes your pictures down.

I will that say that having more pixels can be important if you plan on significant cropping — which I advise.

Social media platforms can support different photo dimensions, but each has its own clearly ideal ratio. I find being able to flexibly crop my images is only becoming more important as the lines between major social media platforms continue to blur (does anyone post on just one site anymore?). This means I need photos with a decent amount of pixels and a reasonably wide shot.

It’s tempting, I know. The more pixels, the higher the resolution. And the more you know what you’re doing, the more a higher resolution image means to you when taking, selecting and editing your images.

But just like getting a DSLR won’t make you a good photographer, having more pixels won’t automatically make your pictures any good.

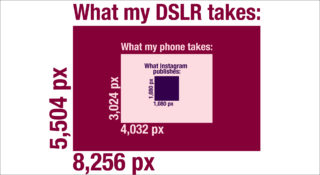

In fact, the amount of pixels we cram into the images we take today are downright wasteful. To understand just how egregiously enormous the images we take are, compared to what size they have to be for us to actually share them, enjoy the infuriating diagram below.

Using the D850, the 45.7-MP camera captures images that are 8,256 pixels wide by 5,504 pixels high. The 12-MP rear camera in my Samsung Galaxy S9 captures images that are 4,032 pixels wide by 3,024 pixels high. When I post an image to Instagram, a picture taken on my phone is shrunk about 11 times smaller — a DSLR image is shrunk about 39 times smaller.

So why bother taking photos that are so enormous? Why go out of our way to require the expensive infrastructure for high-resolution photography (which demands and costs more the higher the resolution)? Why break our backs and our banks getting photos that will be mauled into scraps by a cackling Mark Zuckerberg?

My point exactly.

The damning facts on smartphones

Your smartphone camera will most likely capture about half the amount of pixels as a mid-range DSLR. While most hobby DSLR cameras tout 24 MP, professional-grade cameras nowadays will run around 50 MP. Most iPhones and Androids from the last several years have come with 12-MP cameras, which is, again, 12 million pixels in every single image.

Yet a slew of upcoming smartphones have promised whopping 48-megapixel cameras. Several others are also cramming more cameras with specific lenses into the backs of their phones, including Apple and Huawei’s plans for three-camera phones and Nokia’s leaked five-camera model. I now have to argue that even these smartphone cameras are unnecessary for the picture quality needed in communications.

You can see the power of these smartphone cameras in this commercial, where Wonder Woman (also known as actress Gal Gadot) takes disturbingly invasive images of people from ridiculously far away with the Huawei P30 Pro, a phone that includes lenses of varying focal lengths.

Putting these massive camera sensors on phones isn’t anything new. Back in 2012, Nokia debuted a 41-MP camera on its 808 PureView. There’s a reason why the top phone models in the world didn’t follow suit.

The problem with the 808 PureView was that the 41-MP camera came alongside extremely limited storage space. With an image taken by a 41-MP camera, your picture sucks four to 10 megabytes of storage on your phone. At best, you could store a few hundred photos, if you only ran the operating system in the meantime.

These 40-MP+ cameras aren’t taking pictures with zoom-and-crop metrics, they’re taking pictures with post-on-a-billboard metrics (if you are a billboard photographer, please disregard this segment. The rest of the article still applies).

Fun fact check:

At about 14 feet by 48 feet, billboards are a fair way to conceptualize how large an image could be while still looking sharp. But in reality, billboards are printed at a very low resolution, according to photography education platform Fstoppers.The human eye is limited in how much resolution it can see based on how far it is from the image. Double the distance from the image and you cut in half the amount of detail the human eye can see.

At a distance of around 2,500 feet away, you could only ever perceive 6,048 pixels, or 0.006 MP, of an image. The article concludes that the D850 has about 472 times that in resolution.While storage space on phones has also rapidly grown, the fact remains that most of the time, we don’t need and cannot use the high-resolution images we take, be it with a DSLR or a smartphone.

The DSLR cameras I use take pictures that are massive, require significant infrastructure and are largely destroyed as soon as I try to share them. The cameras are also complicated, expensive, heavy, require constant maintenance and contributed to my carpal tunnel diagnosis at age 22.

But I use DSLRs in my professional and personal lives because I am lucky enough to have these resources available to me, because I know how to use them and, fundamentally, because I love taking pictures.

I believe these are by far the best reasons to use a DSLR in modern-day communications. If none of these reasons apply to you, I recommend changing your mindset. Try looking at your smartphone as the powerful yet manageable photography resource it can be, or as a stepping stone to learning the same science that applies to all photography.

Don’t waste your time, don’t waste your money, don’t waste your pixels. Be aware of your context — think about what you want your images to do and where they will go. Don’t get hung up on getting the best possible technical specs from a camera without thinking about why you want to take pictures in the first place.

Just take the best pictures you possibly can. And tomorrow, go take better ones.